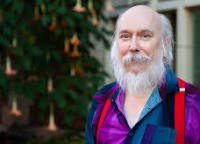

About the IX International Communication Week, ConectaT 2023, we share an exclusive interview with Henry Jenkins, American media academic, currently Professor of Communication, Journalism and Cinematic Arts, and Adjunct Professor at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and at the USC School of Cinematic Arts.

This event will take place at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters of the Universidad Atónoma de Chihuahua, in Chihuahua, Mexico.

They can attend this faculty if they wish, or they can follow the transmissions of the conferences through the Facebook page of the Facultad de Filosofía y Letras.

You can also visit the event website for more information.

- What can you tell us about your next conference that he will give at the Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, within the IX International Communication Week?

The core question is Why does fandom matter. Fandom studies is celebrating its 31st anniversary this year and it is now a global phenomenon. I am in the process of writing a new book which overviews the field and shares my own three decades of research about fans and fandom. What do we know now that we did not know in 1992, which is often cited as the year Fandom Studies emerged as a subfield? How do we conceptualize fans as audiences, subcultures, publics, networks? How does fandom differ from one national or cultural context and another? What does the public still not understand about fan communities?

- Why is it important to analyze the phenomenon of fanaticism?

First, please do not call it fanaticism. This phrase evokes what we are trying to get away from and why this work is so important. In a networked society, more and more people are active fans of one or more media property. Let’s define fans as a community or subculture of people who are passionately engaged with popular culture and who are creative and critical in the ways they engage with media content. In many cases, their fandom experiences can be the starting point for educational experiences, for new forms of shared creative expression, or for religious or political engagements. They are also important economic drivers within the creative industries and beyond, they are strong supporters and some of the deepest critics of the media industries and its policies, especially those regarding IP, privacy, and consumer relations. What they are not, though, are fanatics who are confused about the lines between fantasy and reality; they are not socially isolated; they are not obsessive (at least no more than an academic is about their area of research),

- What relationship does fanaticism have with communication and journalism?

Fandom has been studied from many different perspectives, but media and cultural studies and communication has been an important one. Fans are often early adopters and adapters of new media technologies, and as such, their activities help shape how the rest of us will use digital tools once they are more widely embraced. Fan engagement has become a primary currency driving decisions within the media and creative industries. Fans have developed their own grassroots artworld where they use media content as raw materials for expressing their personal and collective identities.

News media also often cultivates fans who play an active role in circulating content at a time when fewer people sit down to watch the newscast or read the newspaper. Young people are often grazing the news through social media and thus taking on a greater responsibility for keeping each other informed. Many different networks play this role, but fandom is among the most fully established. Moreover, more and more activists are deploying pop culture references (in the form of memes or protest signs) as a means of communicating political concerns and if journalists do not understand these new practices, they are not going where the action is and misreporting especially the political lives of youth around the world.

- Henry, you’ve been a prominent advocate for transmedia narratives and have coined the widely recognized term. Could you briefly explain what “transmedia narratives” exactly means and what you believe its significance is in contemporary culture?

Transmedia, by itself, means any kind of relationship which exists across multiple media. So, we can talk about transmedia characters (the original use of this term), transmedia branding, transmedia activism, transmedia education, etc. I have spent the most time looking at transmedia narratives. Transmedia storytelling represents a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience. Ideally, each medium makes it own unique contribution to the unfolding of the story. Take Marvel, which adopted its comic book characters and stories to the big screen with each new film adding information to our understanding of the Marvel universe. Players deploy that knowledge when they play Marvel games. Increasingly television series for Disney Plus are framing information which will intensify our engagement and shape our understanding going into the next Marvel film. How do things like amusement park attractions at Disneyland fit into this mix? What about plush or vinyl versions of the characters? Or coloring books or…? The result is an expansive universe where many if not all of their products are making significant amounts of money and shaping the cultural lives of millions of fans around the world.

- One of the most intriguing aspects of transmedia narratives is how they enable consumers to actively engage in creating and expanding content. How do you think this active participation affects the traditional relationship between creators and audiences?

Most transmedia franchises have two elements – a cultural attractor (which draws people together) and a cultural activator (which gives them something to do). Minimally, the dispersal of information within the storyworld requires spectators to become hunters and gatherers who seek out and engage with different extensions and bring information back to the tribe (often some kind of online network). Transmedia depends on what I call “additive comprehension,” with each new element adding something meaningful to our experience of the whole. That said, fans do not need producers to “enable” them to participate. Most fandoms are not necessarily around transmedia properties. And some fans complain that companies use transmedia in an effort to control fans by closing off spaces otherwise open to the imagination, setting rules and regulations which govern their participation in these enclosed spaces, or displacing diverse representations for the “mothership” (the primary text in the transmedia system) to orbiting texts (i.e. secondary works). All these problems require close scrutiny which the fan community has to date been the primary group holding transmedia producers accountable.

- As digital technologies have advanced, transmedia narratives have become more prominent across a variety of mediums, from films and TV series to video games and comics. Do you think there are certain forms of media that are especially conducive to creating and developing transmedia narratives, or is it an approach that can be applied to any medium?

The current wave of transmedia has sprung up from conditions of media concentration and networked consumption, but there’s nothing about transmedia that requires either. I would argue that the first human expressions we know of – the cave paintings – were transmedia in that they combined the painting with, we believe, some kind of human performance and new research shows that the paintings were at acoustic hot spots in the caves and thus may have involved human-made sound effects (growls, say) or spoken word. I am currently looking at the transmedia system Tarentino created around Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, which involves his novelization, multiple podcasts, and even the film schedule at the New Beverly Cinema which he owns.

- Transmedia narratives often involve expanding stories across different platforms and media. However, there’s also the risk of important parts of the narrative being lost or inaccessible to certain segments of the audience. How do you address the challenge of maintaining coherence and accessibility in a complex transmedia narrative?

Yes, this is a key risk. I have observed its effects during a visit this summer at Shanghai. They have hit or miss access to even big budget Hollywood films according to their whims. They watch many American films via Pirate Bay, but this requires them knowing that these films exist. Especially for the films they can only access through pirate channels, no one is translating the various transmedia texts, and they may not know they exist so even if they try to reach around the Fire Wall, they may not know to look for them. As a result, the films they see are largely decontextualized. To cite a recent example, the distributors of Barbie had no awareness that it was not a straightforward children’s movie and thus treated it accordingly. But it is being discovered by 20–30-year-old women as an important vehicle for popular feminism, interest is growing online, and they are renting theaters to have fan screenings and discussions. These fan activities are repairing the damage caused by gaps in distribution and education, and as a result, the film which initially came in 5th place the week it launched in China is becoming a slow-build success there.

- The convergence of different media and platforms has led to the creation of rich and expansive narrative universes, as seen in franchises like Star Wars and Marvel. Do you believe there’s a limit to how much a transmedia narrative can expand before the story becomes too fragmented or overwhelming for consumers?

Marvel comics teach us important lessons there. There are some people where there are no limits, where they crave complexity and are happy to watch the stories build out indefinitely. For others, these expanded texts create challenges of jumping on belatedly and so audiences start to decline, Periodically, Marvel reboots its series, get complaints from the hardcore and appreciation from newcomers. For the most casual viewers, who may see one of every three or four Marvel films, they either ignore the transmedia content or complain about having to “do homework” to watch a “popcorn movie.” This is an argument for a more tiered approach with the primary text being self-contained and the other content additive or ancillary, so each film can be watched on its own terms. But there are so many ways to access films on streaming or information on the web now that we expect and can manage much more complexity than we did in the past.

- As we continue to move forward in the digital age, technology will keep evolving and offering new ways of storytelling. How do you envision the future of transmedia narratives? Are there emerging areas or trends on the horizon that you believe will have a significant impact on how narratives are developed and consumed?

I certainly can imagine haptics or immersive theater or Augmented reality becoming a more central aspect of the experience. The approaches are apt to be culturally specific. When I was in China, we did a transmedia world building workshop and students were exploring ways to deploy forms of media particularly popular in China – blind boxes of character goods, themed cafes, even cat cafes, grab machines, and so much more. But the real shaft is going to be in the quality of storytelling as artists learn to deploy these various media in relationship with each other and audiences are better informed about how to trace the connections across different media.